Autor del articulo: Proceso Digital / 31 de Enero 2014 - 11:51

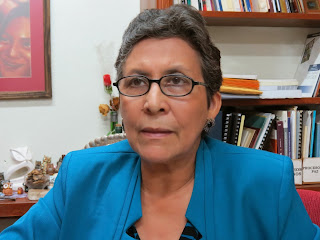

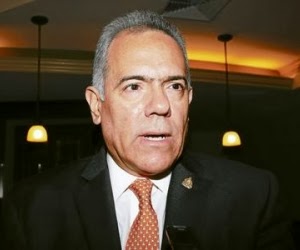

Tegucigalpa - El ex fiscal general del

Estado, Edmundo Orellana, manifestó este viernes que la junta directiva

del Instituto Hondureño de Seguridad Social (IHSS), es responsable de la

crisis que atraviesa esa institución.

“Siempre hay excusas para no asumir la

responsabilidad de los actos, la junta directiva es la que aprueba todas las cosas

financieras de una institución, aprueba el presupuesto, las licitaciones, los

contratos que se firman”, explicó.

En ese

sentido, dijo que la junta directiva también es responsable de lo que ahí paso,

“en este caso del Seguro Social es aún más grave porque la empresa privada ha

venido exigiendo que esa institución fuera dirigida por ellos y la mayoría de

los integrantes de la directiva es del sector privado, y el desastre del

instituto en base es consecuencia del sector privado y no del sector público”,

señaló.

El ex fiscal

del Estado recomendó revisar el sistema de Seguridad Social que existe en el

país.

“A mi juicio

no existe un sistema, lo que hay es un Instituto Hondureño de Seguridad Social,

por lo que el gobierno debe de revisar si es conveniente ese modelo y si sigue

funcionando o si es necesario crear un sistema que el seguro se encargue

simplemente de pagar los servicios médicos hospitalarios de los

derechohabientes”, argumentó.

Agregó que

las autoridades del Seguro Social “no se deben de hacer cargo de edificios,

sindicatos, de contratar personal, sino de establecer un sistema que cada quien

se dedique a lo suyo, en donde los hospitales públicos y privados sean

contratados por el sistema para que todo hondureño pueda llegar no importa de

dónde este y que el seguro pueda pagar”.

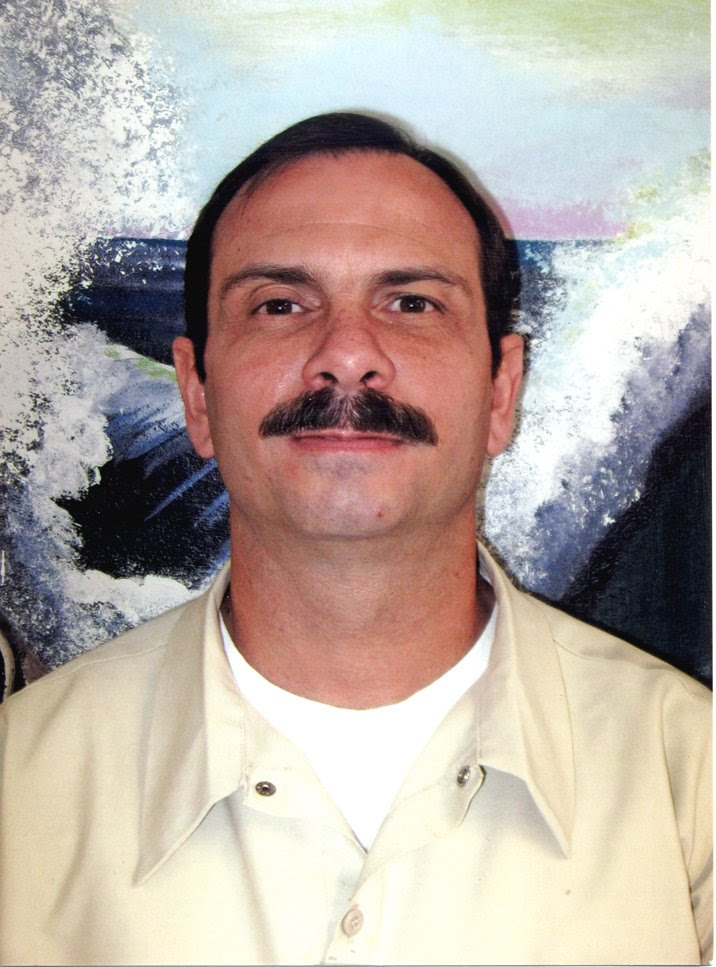

Fernando saldrá de la prisión federal de Safford, en Arizona,

después de cumplir su injusta condena de 15 años, 5 meses y 15 días, resultado

de un amañado procesamiento y juicio por parte del gobierno

estadounidense. Fernando, al igual que sus otro cuatro hermanos:

Gerardo, Ramón, Antonio y René, los Cinco Cubanos, sacrificaron sus vidas para

defender al pueblo cubano de una infame campaña terrorista llevada a cabo por

terroristas de la extrema derecha cubanoamericana radicados principalmente en

Miami, con el conocimiento y la protección de Washington.

Fernando saldrá de la prisión federal de Safford, en Arizona,

después de cumplir su injusta condena de 15 años, 5 meses y 15 días, resultado

de un amañado procesamiento y juicio por parte del gobierno

estadounidense. Fernando, al igual que sus otro cuatro hermanos:

Gerardo, Ramón, Antonio y René, los Cinco Cubanos, sacrificaron sus vidas para

defender al pueblo cubano de una infame campaña terrorista llevada a cabo por

terroristas de la extrema derecha cubanoamericana radicados principalmente en

Miami, con el conocimiento y la protección de Washington.